Learning From What’s Hidden

隠されたものからの学び

In our current “information society” it seems that learning should be easier than ever. If more information actually means greater possibilities for learning, then digital information offers an exponentially expanding horizon, increasing at some 2,300,000,000GB per day worldwide. The hope of “big data” is that we can learn about things we weren’t even asking questions about – novel patterns should emerge from the oceans of information. But there are many paradoxes lurking: What if so much data makes finding meaningful information similar to finding a needle in a haystack? More importantly, who is allowed access and to which information?

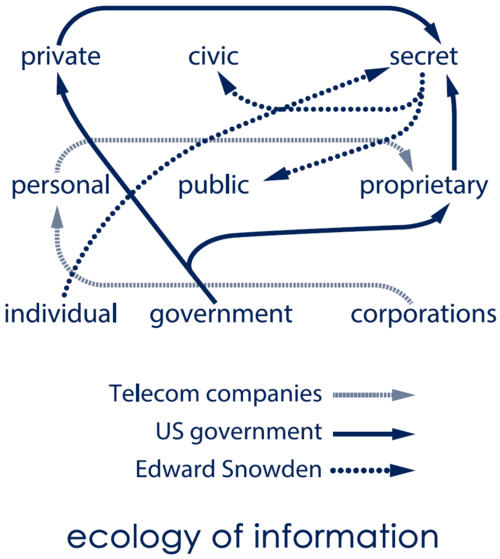

The case of former CIA employee Edward Snowden raised these issues in a dramatic way when he leaked thousands of government files to the public. He revealed that the U.S. had secretly collected enormous amounts of phone and email information thought to be completely private. A year later, it is still not clear if the government’s actions were illegal. Meanwhile, although Snowden has been charged with espionage, recent polls show that 57% of young Americans (ages 18-29) believe that his actions were beneficial and that citizens have a right to know about government surveillance programs. In other words, if Snowden did spy, it was at least to stop other spying.

Perhaps just as interesting, the poll shows that as many as 28% of the people hadn’t heard anything about the leak at all! Snowden’s revelations lose meaning unless they are widely known. Alas, even though information may be available, there is no guarantee that people will necessarily learn anything from what there is to know. Why are so many (especially young) Americans still ignorant about the Snowden leaks? Perhaps it’s harder and harder to distinguish meaningful “signal” among the vast background of “noise” within media today.

How much can be learned without having to break any law? Artist Trevor Paglen has uncovered remarkable details about many secret US surveillance programs and their locations by carefully searching publicly available information. Paglen’s writings, photographs, and sculptures challenge the mysterious aura of “state secrets,” showing how secrecy often hides out in the open: Professional spies are real, but they are the exception. Instead, it is everyday people working for companies and governments who are the ones most responsible for maintaining the systems of surveillance and secrecy that are so troubling and undemocratic.

In Japan, the LDP’s recent creation of a “Designated Secrets Bill” has outraged many because of powers it gives the government to keep information from journalists and the public, as well as punish whistleblowers. Such secrecy laws are deeply troubling when the Japanese government and TEPCO continue to be criticized for the lack of transparency, especially concerning the Fukushima disaster and its related risks. The US government praises the new law because it helps protect its own military and diplomatic information, though at the cost of Japan’s own freedom of the press.

Today’s informationrevolution is an unprecedented opportunity for learning, but like the universe itself, its expansion continues to accelerate. How will we navigate big data, net neutrality, secrecy, and privacy? Of course accurate and open access to the information is crucial, but the most meaningful information will no doubt involve the most risk.

References:

The estimated daily increase in digital information

http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/bigdata/what-is-big-data.html

Opinion poll on Snowden’s secrets leak

http://cdn.yougov.com/cumulus_uploads/document/c3cn5y4itm/tabs_HP_snowden_20140328.pdf

Artist Trevor Paglen

http://www.paglen.com/

Japan’s “Designated Secrets Bill”

http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2013/12/31/258655342/japans-state-secrets-law-hailed-by-u-s-denounced-by-japanese