Learning from What’s Already There: Beyond the Digital Bubble

デジタルバブルを超えて:すでにそこにあるものからの学び

On a recent autumn afternoon my wife, an art professor, was planning to take her first-year college students to a nearby museum. They were on the fourteenth floor of a building and one wall in their room was completely glass, creating a giant window that looked over a wide expanse of the city. It had been raining very hard earlier in the day and she asked out loud whether they should walk to the museum or not.

At that moment, she reports, all 15 of the students looked down at their cell phones to check the weather. Not one actually looked out the windows right in front of them.

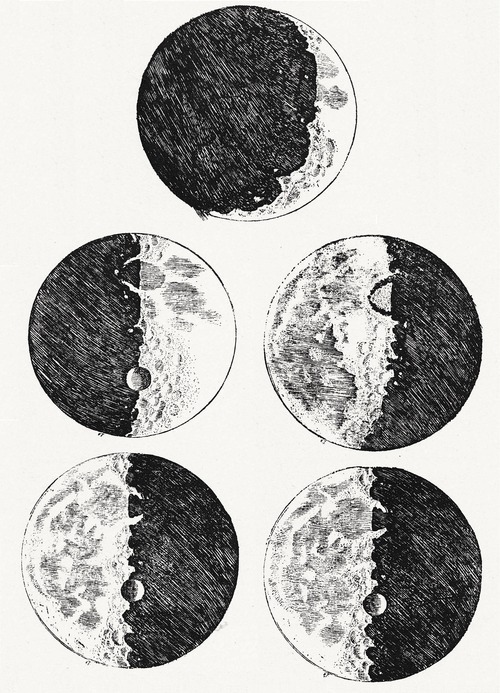

This story seems unbelievable, and at the same time, totally realistic. It captures the deep ironies of our growing dependency on mobile technology and digital information, with profound implications for how we think about learning. It also raises significant questions about the quality of our lived experience itself – what does it mean if we prioritize the phone in our hand to the eyes in our head? Three-hundred years ago philosopher Francis Bacon warned against a culture that followed what he called the “Idols” of rumor, assumption, and second-hand knowledge. Bacon argued that thinkers of his time had “abandoned experience altogether” in favor of the claims found in ancient writings, such as Aristotle. At the very same moment in history, Galileo was fighting condemnation for his telescopic observations that challenged the authority of the Church and the Bible on the earth’s relation to the rest of the universe.

Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidereus_Nuncius#mediaviewer/File:Galileo%27s_sketches_of_the_moon.png

Of course a smartphone is certainly neither the Bible nor an ancient Greek text, but the assumption that the Internet can provide a form of current and collective information that is more meaningful than our own embodied experience is cause for concern. It makes me want to reconsider the word “screen.” In English screen refers to the surface of a TV, computer, or smartphone – a surface on which an image is projected. But “screen” also can describe a mesh, a filter, or a barrier that allows some things in while keeping others things out. Like a screen door that lets the air through but insects away, the digital screen lets the Internet through, but perhaps at the cost of screening off our direct sensory and embodied experiences.

While mobile and web technologies are so compelling and handy for connecting across distances, there are other ways that they can create new forms of distance at the same time. American Internet activist Eli Pariser has argued that the way Internet algorithms, like Google, automatically tailor search results to match the users history creates a filter bubble of biased information. For example, if you have searched for “economic growth,” “mining stocks,” and “benefits of natural gas,” in the past, then when you search for “climate change” you might be more likely to get results that are skeptical of climate change science, and less likely to get sites that discuss the problems of fossil fuels or benefits of renewable energy – all this based on how a search engine determined your personal preferences. In this way, some argue that the Internet has actually resulted in people becoming less open-minded to a diversity of viewpoints and worsened what media theorists call selective exposure to information that suits our existing opinions or worldview.

Students checking the weather on their phones or the selective information that is fed to us from the internet: in both cases the crucial question is about the general “digital bubble” that we are living more within every day. If we think that learning prioritizes a process of outward exchange – between ourselves and the environment or ourselves and other people – then the problem with the digital bubble is its tendency to prioritize an inward-looking form of consumption over engaging with the world already around us.

Rule #238 for digital living: Next time you think it might be raining, first look up at the sky, and only then down at your phone!