Learning Through the Anthropocene (Part 2)

アントロポセン(人類の時代)からの学び(その2)

If the Anthropocene is a new geological epoch in which “nature” and “culture” are no longer separable — either conceptually or materially — then what is the status of traditional ideas like “aesthetics” that have historically relied on those distinctions? With shrinking natural resources, growing populations, increased connectivity but also growing social inequalities, what aesthetic forms within our media ecology will be generative of new and meaningful sense?

While the German Romantics cultivated the notion of “aesthetics” as “beauty,” the term aesthetics has its etymological roots in Greek, where its foundational meaning is the ability to “sense” or “perceive” more generally. Many of the images that have helped us perceive the unprecedented changes to the Anthropocenic Earth are thanks to technologies of “remote sensing” — satellites and sensors of every kind with the power to observe physical dynamics at large scales. Through such technologies, everything from the clearing of the Amazonian rainforests and the dynamics of global weather patterns, to the desperate migration of millions of refugees across Europe and the Mediterranean, can be tracked in detail and at a distance.

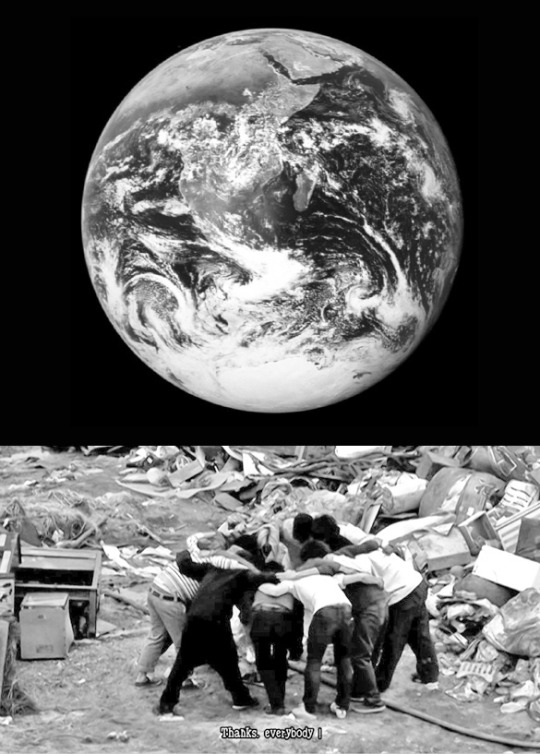

The Blue Marble is arguably the most iconic of remote sensing images, a picture of the whole Earth taken by astronauts in 1972 (see Figure). An encompassing view, the Blue Marble would seem like the most “realistic” of all pictures, and an ideal image for the Anthropocene: aesthetically compelling, data-rich, and contemplative because it visualizes the finite planetary boundaries of “spaceship Earth.” But the Blue Marble is also extremely abstract, reducing all of the detailed and complicated dynamics into a smoothened and singular view.

Do images of the current migration crisis captured by photojournalists succeed any better? Although they are proximate and on a human scale, such images are often just as remote to us as a view from outer space — both represent situations most of us simply never personally experience. Images of either kinds provide some perception of events, but they lack the feeling of personal participation that is necessary to truly sensitize us to these situations. How can we make our sensing less remote in an Anthropocene that is thought to demand a new level of sensitivity and responsiveness?

Projects in the UK like Forensic Architecture and Citizen Sense exemplify an approach that makes use of images and data from inexpensive cameras or sensors in a way that allows people to interpret acts of pollution, military conflict, or other complex events. Rather than just “see” the world, these projects allow citizens to closely analyze political and environmental situations for themselves, giving birth to new forms of investigative, grassroots, and research-based aesthetics of participation. Storyplacers and Media Conte, on the other hand, try to make use of mobile & digital media platforms as a means of engaging personal narratives of place and community. Not only is the idea to create records of experience, but also to potentially mobilize self-organization and spur social movements around matters of local concern.

But just as aesthetically important may be projects like AI-KI 100 (100 Cheers) , by the Japanese art collective Chim Î Pom. Visiting Soma City soon after the 2011 Tohoku disaster, the art collective collaborated on a performance with a group of local residents. Huddled arms-together in the midst of a ravaged landscape they yelled whatever came to their mind, from the inspirational to the absurd: “Go Tohoku!” “Soma makes great strawberries!” “I want to wear a swimsuit!” “30 micro Sieverts!” The cheers were an aesthetic response that expressed hopes, frustrations, and fears to create forms of participation and awareness as direct as they were empathetic.

As Chim Î Pom puts it, the Soma City residents were both the victims of the disaster as well as their own aid workers; rather than being “remote” to the situation, they were exactly in the middle of it as participants. Perhaps something similar can be said for Earthlings experiencing the uncertainties of the purported Anthropocene — we in the middle of it; as its perpetrators, its potential victims, and our own rescuers alike. The new media for this new epoch will require aesthetic forms that are collectively meaningful but less remote, forms that can make sense of the world as not just information, but also as complex, lived experiences beyond the bounds of data.

References:

“The Blue Marble” image from 1972, NASA.

http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view.php?id=55418

The “Forensic Architecture” project at Goldsmiths, University of London.

http://www.forensic-architecture.org/

The “Citizen Sense” project at Goldsmiths, University of London.

http://www.citizensense.net/

The “Storyplacers” project (Japan/Finland collaboration).

http://storyplacers.tumblr.com/About

メディアコンテ / Media Conte

http://mediaconte.net/

Video of Chim Î Pom’s “KI-AI 100.”

http://video.pbs.org/video/2071709279/